Ready to Begin?

Transform your research writing skills with our comprehensive, practical approach. Each chapter builds on the previous one, so we recommend following the suggested order for the best learning experience.

Your comprehensive guide to writing impactful review papers

This course will transform you from someone who struggles with review writing into a confident author who can synthesize literature effectively and create compelling scholarly works.

Start with understanding what review papers are, their types, and who can write them. This builds your conceptual foundation.

Learn the essential components and organization of professional review papers, including abstracts and keywords.

Master the art of creating compelling, searchable titles that attract readers and accurately represent your work.

Learn professional practices for listing authors, managing contributions, and handling correspondence.

Hands-on activities and practical exercises in every chapter

See good vs. bad examples with detailed explanations

Mentor insights and professional advice throughout

Checklists, templates, and step-by-step guides

Transform your research writing skills with our comprehensive, practical approach. Each chapter builds on the previous one, so we recommend following the suggested order for the best learning experience.

"This course transformed my approach to review writing. The step-by-step guidance and practical examples made complex concepts easy to understand and apply."

Master the art and science of writing comprehensive review papers that synthesize existing research and contribute meaningful insights to your field.

A review paper is not an original publication in the usual sense, though it can be valuable scholarship. On occasion, a review will contain new data (from the author's own laboratory) that have not yet appeared in a primary journal. However, the purpose of a review paper is to review previously published literature and to put it into perspective.

A review paper is oftentimes long, often ranging between 10 and 50 published pages. (Some journals now print short "mini reviews.") The subject is fairly general, compared to that of research papers, and the literature review is, of course, the principal product.

However, the really good review papers are much more than annotated bibliographies. They offer critical evaluation of the published literature and often provide important conclusions based on that literature.

The organization of a review paper usually differs from that of a research paper. The introduction, materials and methods, results, and discussion arrangement traditionally has not been used for the review paper. However, some review papers are prepared more or less in the IMRAD format; for example, they may contain a methods section describing how the literature review was done.

Review papers are scientific articles that summarize and synthesize existing research on a particular topic. They are different from original research papers because they don't present new experiments or data; instead, they provide a comprehensive overview of what's already known. Here are the main types of review papers:

This type of review gives a broad overview of a topic, summarizing the findings from many different studies. It is often qualitative and can be somewhat subjective because the authors decide which studies to include and how to interpret them.

This type of review uses a structured and methodical approach to search, select, and critically analyze all relevant studies on a particular topic. It aims to minimize bias and provide a more objective summary.

This type of review aims to map the existing literature on a broad topic, identifying key concepts, theories, sources, and gaps in the research. It is less detailed than a systematic review and is often used to clarify working definitions and conceptual boundaries.

Review papers bring together scattered pieces of research to create a comprehensive understanding of a topic, helping readers see the bigger picture.

They identify gaps in current knowledge and suggest future research directions, guiding the scientific community toward important questions.

Good review papers don't just summarize—they critically evaluate studies, assess methodologies, and draw meaningful conclusions from the evidence.

They save researchers time by providing curated, analyzed information rather than requiring them to read hundreds of individual studies.

Throughout this course, you'll learn to craft review papers that not only summarize existing research but also provide valuable insights, identify research gaps, and contribute meaningfully to your field of study.

Master the structure and understand different types of review papers

Learn to create compelling titles and organize author information

Develop skills in writing abstracts, introductions, and methodology sections

Present results, discuss findings, and draw meaningful conclusions

Perfect references, formatting, and prepare for publication

Think of a review paper as being a knowledgeable guide in a vast library. Your job isn't just to point out interesting books (studies) but to help visitors understand the connections between them, identify the most valuable insights, and suggest where to explore next. Quality synthesis beats quantity of sources every time.

Learn the fundamental architecture of review papers and understand the essential components that create a professional, well-organized academic document.

Understanding the proper structure of a review paper is crucial for creating a document that meets academic standards and effectively communicates your research synthesis to readers.

Follow this structured template for professional review paper organization:

The title should be concise, descriptive, and capture the essence of your review topic.

This structured approach ensures that readers can quickly grasp the key elements of the research without having to read the entire paper.

Provides a brief background and context for the study.

States the purpose or objective of the research.

Describes the methods and procedures used to conduct the study.

Summarizes the main findings or outcomes of the research.

Interprets the results and discusses their implications.

Concludes with the main takeaways or contributions of the study.

Keywords are terms or phrases that succinctly capture the main topics or themes of a document, making it easier for readers to identify its content.

Help readers find your paper through database searches

Enable proper categorization in academic databases

Allow rapid content assessment by potential readers

Ensure each section flows naturally into the next, creating a coherent narrative throughout your review.

Maintain appropriate proportions between sections, giving adequate space to each component.

Each section should have a distinct purpose that contributes to the overall review objectives.

Follow academic formatting standards for headings, citations, and overall presentation.

Use standard academic fonts (Times New Roman, Arial) consistently throughout the document.

Maintain clear distinction between different heading levels using appropriate formatting.

Use justified text for body content and appropriate alignment for headings and captions.

Use consistent numbering for sections, subsections, and references throughout the paper.

Maintain appropriate line spacing, margins, and paragraph breaks for readability.

Format tables and figures consistently with proper captions and numbering.

Before finalizing your review paper structure, ensure:

A well-structured review paper is like a well-designed building – every component has its place and purpose. Start with a solid foundation (clear title and author information), build strong walls (comprehensive abstract and relevant keywords), and ensure everything connects seamlessly. Structure first, content follows.

Learn the art and science of crafting compelling, discoverable, and professional titles that capture attention and communicate your research effectively.

In preparing a title for a paper, you would do well to remember one salient fact: This title will be read by thousands of people. Perhaps few people, if any, will read the entire paper, but many people will read the title, either in the original journal, in one of the secondary (abstracting and indexing) databases, in a search engine's output, or otherwise.

We define it as the fewest possible words that adequately describe the contents of the paper.

Remember that the indexing and abstracting services depend heavily on the accuracy of the title, as do individual computerized literature-retrieval systems. An improperly titled paper may be virtually lost and never reach its intended audience.

The meaning and order of the words in the title are important to the potential reader who sees the title in the journal table of contents. But these considerations are equally important to all potential users of the literature, including those (probably a majority) who become aware of the paper via secondary sources.

The title should be useful as a label accompanying the paper itself, and it also should be in a form suitable for the machine-indexing systems used by Chemical Abstracts, MEDLINE, and others. In short, the terms in the title should be those that highlight the significant content of the paper.

Perhaps the most common error in defective titles, and certainly the most damaging one in terms of comprehension, is faulty syntax (word order). All words in the title should be chosen with great care, and their association with one another must be carefully managed.

From the author's point of view, a good and catchy title is essential for several reasons:

Authors want their work to be read and appreciated. A catchy title can draw readers in, increasing the chances that they will engage with the content.

Authors often have specific messages or insights they want to convey through their work. A well-crafted title can succinctly capture the essence of the piece, effectively communicating its purpose to the audience.

A strong title can contribute to the credibility of the author and their work. It demonstrates professionalism and attention to detail, instilling confidence in readers that the content will be worth their time.

In fields with a lot of competing literature, authors want their work to stand out. A catchy title can distinguish their piece from others on similar topics, helping it to gain recognition and visibility.

Authors want readers to be interested in their work and to engage with it deeply. A catchy title can spark curiosity and intrigue, motivating readers to explore the content further and perhaps even share it with others.

When selecting a review topic, it is important to avoid topics that are either too broad or too narrow. The ideal topic strikes a balance—it is focused enough to be manageable but broad enough to provide sufficient material for critical analysis.

Example: "All aspects of diabetes"

Problem: This is overly broad because it encompasses numerous physiological mechanisms, complications, and treatment strategies, which cannot be thoroughly analyzed in one paper.

Example: "Effect of vitamin B12 on insulin secretion in a single animal study"

Problem: Such a narrow focus may not provide enough literature to review or draw meaningful conclusions.

Example: "Role of vitamins in managing type 2 diabetes"

Why it works: This allows discussion of multiple studies, trends, and gaps in the literature while maintaining focus.

Selecting a topic with the right scope ensures that the review is both comprehensive and coherent.

When choosing a review topic, it is important to align it with your supervisor's expertise and current research trends.

A supervisor's guidance is invaluable because they can provide insights on the relevance, feasibility, and depth of the topic, as well as suggest key references or research gaps. Selecting a topic that matches their expertise ensures you receive meaningful mentorship throughout the review process.

At the same time, the topic should reflect current research trends in the field, focusing on areas that are actively studied and of interest to the scientific community. This increases the impact and relevance of your review, making it more likely to contribute to ongoing discussions and attract publication opportunities.

By balancing the supervisor's guidance with contemporary trends, students can choose a topic that is both feasible and scientifically significant.

A good rule of thumb is to aim for a title that is no more than 10-12 words or around 70 characters. This ensures that the title is clear, readable, and effectively conveys the main focus of the work.

We define it as the fewest possible words that adequately describe the contents of the paper.

If you prefer your title to be in all uppercase and bold without any special characters or syntax, you can achieve all above things mentioned.

Now that you've understood what makes a title effective, it's time to apply the principles. Follow these steps to practice:

Choose any recent research paper (or even a classroom project) you've worked on.

Write your first attempt without overthinking.

Apply the rules you've learned: keep it concise, clear, and accurate.

Read your title aloud. Does it make sense instantly, without confusion?

Share your title with a friend or classmate. Ask: "Can you guess what my paper is about from the title alone?"

Adjust word order, remove jargon, and make sure the most important terms appear first.

"A Study on Herbal Medicine"

Problems:

"Evaluation of Andrographis paniculata and Glycyrrhiza glabra Extracts in Accelerating Wound Healing in Diabetic Rats"

Strengths:

Always create multiple title drafts. The first draft is rarely the strongest—the best titles usually appear after refining and testing. A strong title works like a headline—it should inform, attract, and stand out while staying professional.

Practice Creating Your Perfect Title:

Describe your research topic here...

Write your first title attempt...

Write your improved title here...

Before locking in your title, ask yourself:

Learn to write compelling abstracts that capture the essence of your research and engage readers effectively.

An abstract is a concise summary of a research paper or article that provides readers with a brief overview of the study's purpose, methods, results, and conclusions. It serves as a snapshot of the entire work, allowing readers to quickly understand the main points without having to read the entire paper. The abstract is typically located at the beginning of the paper and provides a glimpse into the content, helping readers decide whether the paper is relevant to their interests and worth reading in full.

Explore the world of descriptive abstracts, your gateway to understanding humanities, social sciences, and psychology essays! These compact summaries, usually spanning 50-100 words, offer a glimpse into the essence of a paper.

They're like little windows into the scholarly world, providing vital insights into the paper's background, its purpose, and the specific focus or interest it addresses. Think of them as storytelling capsules, condensing the key elements of a paper into a concise yet illuminating narrative.

Step into the realm of informative abstracts, where science, engineering, and psychology reports come to life! These comprehensive summaries, typically around 200 words, serve as your compass in navigating the vast landscape of research.

Each sentence is a carefully crafted roadmap, guiding you through the essential components of the paper. From setting the stage with background information to outlining the research's aim or purpose, informative abstracts lay the groundwork for your journey. They then lead you through the intricacies of the research method, unveil the tantalizing findings and results, and culminate in a satisfying conclusion.

Provides a brief background and context for the study.

States the purpose or objective of the research.

Describes the methods and procedures used to conduct the study.

Summarizes the main findings or outcomes of the research.

Interprets the results and discusses their implications.

Concludes with the main takeaways or contributions of the study.

Key Point: This structured approach ensures that readers can quickly grasp the key elements of the research without having to read the entire paper.

A Graphical Abstract is a single, concise, and visually appealing image that serves as a quick summary of a scientific paper, designed to capture a reader's attention and communicate the core message at a glance. It acts like a visual elevator pitch for your research, allowing other researchers to immediately determine the article's relevance before reading the full text.

Self-explanatory figure—a diagram, flowchart, or illustration

Increase visibility and impact of research by making it immediately accessible

Present the essential process, key findings, or major conclusion instantly

A graphical abstract showing how AI algorithms analyze patient data to provide personalized treatment recommendations.

Keywords (Relevant Terms for Indexing) are specific words or short phrases that serve as a compact, technical summary of a document's core content, concept, and methodology, and their primary function is to facilitate indexing and discoverability within academic databases and search engines.

Act as digital tags that enable information retrieval systems to match search queries to relevant papers

Allow researchers to quickly find work without reading the full text

Increase visibility and potential citation count by reaching interested audiences

Just like some stories are short and some are long, abstracts can also be different lengths. But generally, an abstract is like a mini-story, so it's usually not too long. It's just enough to tell someone what the big story (or paper) is about, but not too much that it gives away everything.

Imagine if we write stories in different ways, like with different fonts or colors. Well, abstracts also have their own special way of being written. They start with a short introduction, then talk about what the story (or paper) is about, what the main characters (or subjects) did, what happened in the end, and what we learned from it.

When we write an abstract, we need to think about making it clear and easy to understand. We want to tell people what the paper is about without using too many big or complicated words. It's like telling a friend about a cool new game you played—you want to make sure they understand and get excited about it too!

Try this hands-on exercise to practice writing abstracts:

Pick a recent assignment, experiment, or research topic.

Summarize the topic, purpose, and focus in 50–100 words.

Include background, methodology, key findings, and conclusion in ~200 words.

Check which version conveys your work more effectively.

Share your abstracts with a classmate. Ask if they can understand the research purpose quickly and grasp key findings without reading the full paper.

Your abstract is your research in a nutshell. Keep it clear, concise, and compelling. Highlight the what, why, how, and results, and make every word count. Write it last, polish it first, and test it—if a peer gets it instantly, you've nailed it.

Writing the introduction of a paper is a critical step as it sets the stage for your research and engages your readers. A well-crafted introduction serves as the gateway to your research, guiding readers from general concepts to your specific study objectives.

The opening of your paper is crucial as it sets the tone and engages the reader right from the start. To create an effective hook, you need to present something that captures attention and piques curiosity. Here are several strategies you can use to achieve this:

Presenting an unexpected fact or statistic can immediately intrigue the reader and encourage them to continue reading. This approach works well because it provides concrete information that highlights the importance or relevance of your topic.

"Did you know that more than half of the world's population relies on traditional medicines for their healthcare needs? This surprising fact highlights the crucial role of medicinal plants in global health."

Asking a question at the beginning can engage the reader by prompting them to think about the topic. This method is effective because it invites readers to reflect on their own knowledge or assumptions.

"What if the cure for the next major disease is hidden in the rainforest? This question drives our exploration into the medicinal properties of indigenous plants."

Using a quote from a well-known figure or a respected source related to your topic can lend authority to your introduction and draw readers in. The quote should be directly relevant to the subject of your paper.

"As Hippocrates once said, 'Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.' This ancient wisdom underscores the modern quest to unlock the medicinal secrets of plants."

Telling a short, relevant story can humanize your topic and make it more relatable to the reader. This approach is particularly effective for topics that have a personal or societal impact.

"In a remote village, a mother prepares a herbal remedy from locally sourced plants to treat her child's fever, illustrating the enduring reliance on traditional medicine in many parts of the world."

Painting a vivid picture with words can captivate the reader's imagination and draw them into the world of your research. This technique is particularly useful for topics that involve rich details or complex environments.

"Imagine a lush, green forest, teeming with life and secrets waiting to be uncovered. This vibrant ecosystem is not just home to countless species but also to potential cures for diseases that have plagued humanity for centuries."

You can also combine these techniques to create an even more compelling hook. For example, starting with a surprising fact followed by a thought-provoking question can be highly effective.

"Did you know that more than 80% of the world's biodiversity is contained within rainforests? What untapped medicinal treasures might we discover within these dense and diverse ecosystems?"

By using these strategies, you can create a powerful opening that grabs your reader's attention and sets the stage for the rest of your paper. The goal is to make the reader curious and eager to learn more about your research and findings.

After capturing the reader's attention with a compelling hook, the next step in your introduction is to provide background information. This section sets the context for your study, helping readers understand the broader landscape in which your research is situated.

Begin by offering a general overview of the topic. Explain its significance and relevance in the current field of study. This helps readers who might not be familiar with the subject understand why it is important.

"Traditional medicine, particularly those derived from plants, has been an integral part of human healthcare for centuries. Many cultures around the world have relied on the healing properties of plants to treat a variety of ailments, from common colds to more severe conditions."

Summarize key findings from existing research related to your topic. This shows that you are building on a foundation of established knowledge and helps to position your work within the context of what has already been studied.

"Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of numerous plant-based treatments. For instance, the bark of the willow tree has been used for pain relief for hundreds of years, a practice which eventually led to the development of aspirin."

Point out any gaps or limitations in the current research. This highlights the need for your study and establishes the specific contribution your work will make to the field.

"Despite these advances, there remains a significant gap in scientific validation for many other traditional remedies. For example, the therapeutic potential of plant X, widely used in certain cultures, has not been thoroughly investigated."

Define any important terms or concepts that will be central to your paper. This ensures that all readers, regardless of their background knowledge, can follow along with your discussion.

"Plant X, known scientifically as Y, is a perennial herb native to Z regions. It has been traditionally used for its purported anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties."

Discuss why your research is particularly relevant or timely. This can include the potential impact of your findings on the field, on policy, or on practical applications.

"Understanding the medicinal properties of plant X could lead to new, effective treatments for inflammatory and infectious diseases, offering affordable healthcare solutions in low-income regions."

Complete Background Section: "Traditional medicine, particularly those derived from plants, has been an integral part of human healthcare for centuries. Many cultures around the world have relied on the healing properties of plants to treat a variety of ailments, from common colds to more severe conditions. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of numerous plant-based treatments. For instance, the bark of the willow tree has been used for pain relief for hundreds of years, a practice which eventually led to the development of aspirin. Despite these advances, there remains a significant gap in scientific validation for many other traditional remedies. For example, the therapeutic potential of plant X, widely used in certain cultures, has not been thoroughly investigated. Plant X, known scientifically as Y, is a perennial herb native to Z regions. It has been traditionally used for its purported anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties. Understanding the medicinal properties of plant X could lead to new, effective treatments for inflammatory and infectious diseases, offering affordable healthcare solutions in low-income regions."

After providing the necessary background information, the next step in your introduction is to clearly state the problem your research addresses or the primary research question you aim to answer. This part is crucial because it defines the focus of your study and highlights the specific issue your paper will tackle.

Start by describing the specific problem your research addresses. Make sure it's clearly stated so that readers understand the issue at hand. Explain why this problem is significant and worth investigating.

"Despite the widespread use of plant X in traditional medicine, there is a lack of scientific evidence to support its purported anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties. This gap in knowledge limits the potential development of effective, plant-based treatments for inflammatory and infectious diseases."

Discuss the potential negative impacts or consequences of the problem if it remains unresolved. This helps to emphasize the importance of your research and its potential contributions to the field.

"Without rigorous scientific validation, the therapeutic claims of plant X remain unsubstantiated, leading to missed opportunities for developing new treatments and improving healthcare outcomes, especially in regions where access to conventional medicine is limited."

State the primary research question or hypothesis that your study aims to address. This question should be specific, clear, and focused, guiding the direction of your research.

"This study aims to investigate the medicinal properties of plant X by addressing the following research question: Does plant X possess significant anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties that can be scientifically validated?"

Briefly outline the main objectives of your research. These should align with your research question and provide a roadmap for what your study aims to achieve.

"To address this question, our research will focus on three main objectives: 1) To analyze the chemical composition of plant X, 2) To evaluate its anti-inflammatory effects through laboratory experiments, and 3) To assess its antimicrobial activity against a range of bacterial strains."

Highlighting the importance of your study is essential to convince readers of its value and potential impact. This section explains why your research matters and what contributions it can make to the field.

Discuss how your research can influence the field, solve problems, or lead to new discoveries. Highlight any practical applications or benefits that may result from your study.

"Understanding the medicinal properties of plant X could revolutionize the treatment of inflammatory and infectious diseases. By providing scientific validation for its traditional uses, this research could lead to the development of new, affordable treatments that are accessible to underserved populations."

Point out the specific gaps in existing knowledge that your research aims to fill. This demonstrates that your study is addressing a crucial need and contributing to the advancement of the field.

"Currently, there is a significant gap in scientific knowledge regarding the efficacy of many traditional medicinal plants, including plant X. By systematically investigating its properties, this study will provide valuable insights that are currently missing in the literature."

If applicable, discuss the broader societal or economic implications of your research. This can include improving public health, reducing healthcare costs, or contributing to economic development.

"In many low-income regions, access to conventional medicines is limited. Validating the therapeutic properties of plant X could offer a cost-effective alternative for treating common ailments, thus improving healthcare outcomes and reducing financial burdens on these communities."

Explain how your study introduces new ideas, approaches, or technologies. Highlighting the innovative aspects of your research can further emphasize its importance.

"This study employs a novel combination of advanced analytical techniques to uncover the bioactive compounds in plant X. This innovative approach not only enhances our understanding of plant X but also sets a new standard for research in ethnobotany."

Show how your study fits into larger research trends or goals within your field. This helps to position your work within a broader scientific context and underscores its relevance.

"This research aligns with the global effort to explore and document traditional medicinal knowledge, preserving it for future generations while harnessing its potential to address contemporary health challenges."

Select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study.

Use one of the techniques (fact, question, quote, anecdote, or imagery) to create an engaging opening.

Include key terms, context, and prior research to set the stage for your study.

Clearly define the problem and list your research objectives.

Highlight why your study matters and what contributions it will make.

Compare your introduction with a published paper—what works and what could be improved?

"Your introduction is your research's first impression—make it count! Hook readers, set the context, spotlight the gap, and clearly state your purpose. Be concise, compelling, and confident—if your introduction shines, the rest of your paper will follow."

Practice Writing Your Introduction:

Write your complete introduction here, incorporating all the elements: hook, background, problem statement, and importance...

Before finalizing your introduction, ensure:

The "Material and Method" section of a research paper is crucial because it provides a detailed account of how the study was conducted. This section allows other researchers to understand and replicate your work, ensuring the study's validity and reliability.

In a review paper, the "Material" section typically doesn't involve physical items, biological specimens, or equipment. Instead, it focuses on the sources of information and the methods used to gather, select, and analyze those sources. Here's how to effectively present the material for a review paper:

When writing a review paper, authors must be aware of the different sources of information available to gather accurate and relevant literature. Primary sources are original research articles, clinical trials, case studies, and experimental reports where the data and findings are presented for the first time. These sources are highly valuable because they provide firsthand information and allow critical analysis of methodologies and results.

Secondary sources include review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and book chapters that summarize or interpret findings from primary studies. These are useful for understanding trends, identifying research gaps, and obtaining a broader perspective on a topic. Tertiary sources such as encyclopedias, textbooks, handbooks, and databases compile and summarize information from primary and secondary sources and are helpful for background information and definitions.

In addition to published literature, authors can also use gray literature, which includes reports, theses, conference proceedings, government publications, and technical documents that may not be formally published in journals. Gray literature is important for accessing the most recent data, especially in emerging research areas. Online resources, institutional repositories, and professional organizations are other potential sources for credible information.

Sources of Information: "The review included peer-reviewed research articles, review articles, books, and official reports published between 2000 and 2023. Key databases such as PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched to identify relevant studies."

| Database | Focus Area | Best Use |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | Biomedical and life sciences | Access to research articles, clinical trials, reviews |

| Scopus | Multidisciplinary | Citation tracking, identifying influential studies |

| Web of Science | Multidisciplinary | Citation analysis, impact measurement, literature search |

| Google Scholar | Broad, multidisciplinary | Preliminary searches, gray literature, theses, conference papers |

| Embase | Biomedical and pharmacological research | Drug studies, pharmacology, clinical trials |

| Cochrane Library | Evidence-based medicine | Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, clinical trials |

| ScienceDirect | Scientific and technical research | Full-text access to journals across multiple disciplines |

A well-planned search strategy is crucial for conducting a comprehensive and efficient literature review. The search strategy involves defining the keywords, using Boolean operators, and applying standardized terms like MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) to ensure relevant results.

Main concepts related to research topic

AND, OR, NOT for refining search

Standardized terminology

Date, language, study type

Search Strategy: "Search terms included 'medicinal plants', 'anti-inflammatory properties', 'antimicrobial activity', and 'traditional medicine'. Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) were used to combine terms and refine the search. Filters were applied to include only English-language articles and exclude non-peer-reviewed sources."

Selection Criteria in a review paper refers to the rules and standards used to decide which studies to include or exclude. It ensures that only relevant, high-quality, and focused literature contributes to the review.

Factors that make a study suitable for your review:

Factors that rule out studies:

Selection Criteria: "Studies were included if they investigated the medicinal properties of plant X, involved human or animal subjects, and provided clear methodology and results. Studies were excluded if they were review articles without new data, case reports, or editorials."

Data extraction is a systematic process of gathering and organizing important information from the selected studies included in a review paper. Instead of reading articles in a scattered way, the author collects specific details in a structured format.

| Sr. No. | Author & Year | Study Design | Population/Sample | Intervention/Exposure | Comparator/Control | Outcomes Measured | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||||

| 2 |

Data Extraction: "Data extracted from each study included authors, publication year, study design, sample size, interventions, outcomes, and key findings. Data was recorded in a standardized extraction form using Microsoft Excel."

Analysis in a review paper is the stage where the extracted data from different studies is examined, compared, and interpreted to answer the research question. It goes beyond simply summarizing articles — the author looks for patterns, similarities, differences, and gaps across the selected literature.

Compare results of studies with similar objectives

Highlight agreements or contradictions in findings

Evaluate the quality and strength of evidence

Identify limitations in existing research

Organize findings into themes or categories

The purpose of analysis is to synthesize knowledge, not just list studies. It helps in drawing meaningful conclusions, identifying research gaps, and suggesting future directions. A strong analysis shows the reviewer's critical thinking and makes the paper valuable for readers.

Analysis: "A qualitative synthesis was conducted to summarize the findings of the included studies. Thematic analysis was used to identify common themes and trends in the literature."

Materials: "The review aimed to assess the anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties of plant X by synthesizing existing research.

In a review paper, the "Methods" section outlines the procedures and strategies used to gather, select, and analyze the literature. This section is crucial for ensuring the transparency and reproducibility of your review.

Describe the strategy used to search for relevant literature. This includes the databases searched, the search terms used, and any filters applied to narrow down the results.

Literature Search Strategy: "A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. The search terms included 'medicinal plants', 'anti-inflammatory properties', 'antimicrobial activity', and 'traditional medicine'. Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) were used to combine terms. Filters were applied to include only English-language articles published between 2000 and 2023."

Clearly state the criteria used to include or exclude studies from your review. This ensures that readers understand the scope and focus of your review.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: "Studies were included if they investigated the medicinal properties of plant X, involved human or animal subjects, and provided clear methodology and results. Exclusion criteria were review articles without new data, case reports, editorials, and studies not published in English."

Explain the process used to extract data from the selected studies. Mention what specific data points were collected and how they were recorded.

Data Extraction Process: "Data from the included studies were extracted using a standardized form. Extracted data included the study's authors, publication year, study design, sample size, interventions, outcomes measured, and key findings. Data was recorded in Microsoft Excel for further analysis."

If applicable, describe any methods used to assess the quality of the included studies. This can include tools or checklists used to evaluate study design, bias, and other factors.

Quality Assessment: "The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. Each study was evaluated for potential sources of bias, including selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, and reporting bias. Studies were rated as low, unclear, or high risk of bias based on predefined criteria."

Detail how the extracted data was synthesized to draw conclusions. This can include qualitative synthesis, meta-analysis, thematic analysis, or other appropriate methods.

Data Synthesis: "A qualitative synthesis was conducted to summarize the findings of the included studies. Thematic analysis was used to identify common themes and trends in the literature. Where possible, a meta-analysis was performed using statistical software to quantify the effects of plant X on inflammation and microbial growth."

Methods: "The review aimed to assess the anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties of plant X by synthesizing existing research. The following methods were used:

Is it experimental, observational, or a review paper?

Include plant samples, chemicals, equipment, or databases for review papers.

Describe extraction, experiments, assays, or literature search strategy.

Include groups, doses, or criteria for inclusion/exclusion.

Mention measurements, instruments, statistical tests, or synthesis methods.

Why did you pick these materials, methods, or analysis techniques?

Could another researcher replicate your study exactly?

"Be the guide you wish others had—write your methods so clearly that anyone can replicate your study. Detail is your credibility; reproducibility is your impact."

Practice Writing Your Materials & Methods Section:

Write your materials and methods section here, following the structure and examples provided above...

Before finalizing, ensure:

The Results section of a review paper presents the findings derived from the literature that was reviewed. It synthesizes and summarizes the data, highlights key patterns or trends, and provides a comprehensive overview of the existing research on the topic.

Begin with a brief introduction that outlines the main areas covered in the results. This helps to orient the reader and provide a clear framework for the section.

Present the synthesized findings from the reviewed studies. Group the results into sub-sections based on themes or categories relevant to your review topic.

Provide a comparative analysis of the findings. Discuss similarities and differences between the studies and highlight any discrepancies or conflicting results.

Include tables, figures, or charts to visually represent the data. This helps in summarizing large amounts of information and making complex data more accessible to the reader.

Identify and highlight key trends, patterns, or insights that emerged from the review. Discuss the implications of these findings for the field of study.

Organize results systematically to provide a clear and comprehensive overview of the findings, making it easier for readers to understand the current state of research on the topic.

Follow this systematic approach to organize and present your research findings effectively, ensuring comprehensive coverage and clear communication.

Present studies demonstrating anti-inflammatory effects with specific findings and active compounds identified

Document antimicrobial properties against various bacterial and fungal strains with specific effectiveness data

Document ethnobotanical findings and traditional medicine applications across different cultures

Address discrepancies and conflicting results, explaining possible reasons for differences

Include tables and figures to summarize large amounts of information effectively

Highlight consistent trends and patterns that emerged from the comprehensive review

Use structured tables to present your findings clearly and systematically. Here's an example of how to organize study results:

Essential columns for effective results presentation

Example structure for presenting study results systematically

| Study | Year | Sample | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study A | 2020 | Rats | Anti-inflammatory |

| Study B | 2018 | Humans | 40% reduction |

Best practices for figures and charts in results

How to present findings with appropriate context

Use this comprehensive checklist to ensure your results section meets all essential quality standards and effectively presents your research findings.

Practice these hands-on activities to strengthen your results presentation skills and develop expertise in data synthesis and analysis.

Task: Organize your findings into main themes or categories

Example approach:

Task: Summarize each theme with clear data points or study outcomes

Example format:

Task: Compare and contrast findings across studies, noting similarities and discrepancies

Consider:

Task: Create a comprehensive results table organizing key study information

Include columns for:

The Discussion section is where you interpret your findings, explain their significance, compare them with existing literature, acknowledge limitations, and suggest future research directions. It's the most challenging yet rewarding part of your review paper.

Explain what your findings mean in the context of your research questions and objectives. Analyze patterns and trends, explain cause-effect relationships, and address unexpected findings.

Compare your findings with existing research to establish context and significance. Highlight agreements with previous studies, explain contradictions, and identify gaps filled by your research.

Acknowledge constraints and limitations that may affect the interpretation of results. Include methodological limitations, sample size issues, data quality concerns, and scope limitations.

Discuss the broader implications of your findings for theory, practice, and policy. Include theoretical contributions, practical applications, policy recommendations, and societal impact.

Suggest areas for future research based on your findings and limitations. Include unexplored research questions, methodological improvements, extended applications, and longitudinal studies.

Clearly articulate why your findings matter and their contribution to knowledge. Include novel insights provided, knowledge gaps addressed, methodological innovations, and field advancement.

Follow this structured approach to create a comprehensive and well-organized discussion section that effectively communicates your findings and their significance.

Begin with a clear statement of your key findings and their significance

Provide in-depth analysis of each major finding

Compare findings with existing studies, explaining agreements and discrepancies

Honestly discuss study limitations and their potential impact

Discuss practical and theoretical implications of your findings

Suggest specific directions for future investigations

Learn to recognize and avoid these common mistakes that weaken the impact and credibility of your discussion section.

Problem: Making claims beyond what the data supports

Solution: Use appropriate language and acknowledge limitations

Problem: Simply restating findings without interpretation

Solution: Focus on meaning and implications, not just facts

Problem: Failing to address conflicting findings

Solution: Acknowledge and explain contradictions

Problem: Superficial analysis without deep exploration

Solution: Provide thorough interpretation and context

Use this comprehensive checklist to ensure your discussion meets all essential quality standards and effectively communicates your research findings.

Practice these hands-on activities to strengthen your discussion writing skills and develop expertise in critical analysis and interpretation.

Task: Take a key finding from your results and write three different interpretations

Steps:

Task: Create a comparison matrix of your findings vs. literature

Create columns for:

Task: Identify and categorize all possible limitations

Categories:

Task: Map implications across different domains

Consider implications for:

The conclusion of your review paper serves as a final summary and synthesis of the main findings, implications, and contributions of your study. It offers closure to your readers by summarizing the key points discussed in the paper and reinforcing the significance of your research.

Begin your conclusion by summarizing the main findings and insights derived from your review. Highlight the most significant results and discoveries that emerged from your analysis.

Reiterate the importance and significance of your findings in the context of the broader research field. Emphasize why your review adds value to the existing literature and how it contributes to advancing knowledge in the field.

Discuss the implications of your findings for theory, practice, or policy. Consider how your research outcomes may inform future research directions, clinical interventions, or public health strategies.

Acknowledge any limitations or constraints of your review and discuss how they may have influenced the interpretation of your findings. Be transparent about the scope of your study and the potential impact of its limitations.

Propose potential avenues for future research based on the gaps identified in your review. Offer recommendations for further investigation or exploration in the field.

End your conclusion with a strong and memorable concluding statement that summarizes the key message of your paper and leaves a lasting impression on your readers.

By following these steps, you can craft a well-structured and impactful conclusion for your review paper. Remember to summarize key findings, reiterate importance, discuss implications, address limitations, suggest future directions, and conclude with a memorable closing statement that reinforces the significance of your research.

Recap the main findings from your review in a concise manner.

Reiterate why these findings are important for the field.

Discuss practical, theoretical, or policy implications.

Acknowledge limitations that might affect interpretation.

Suggest future research directions or studies to address gaps.

End with a strong, memorable concluding statement.

"Plant X is useful and has potential. More research is needed."

Problem: Too vague, lacks specifics, no insights or implications, weak ending.

"In summary, this review highlights the anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties of Plant X. The findings underscore its potential as a natural therapeutic agent for managing inflammation and microbial infections. While limitations such as reliance on published English-language studies exist, these insights provide a foundation for future clinical trials and mechanistic research. By bridging traditional knowledge with modern scientific validation, Plant X emerges as a promising candidate for developing effective, plant-based remedies."

Strength: Structured, specific, acknowledges limitations, emphasizes significance, and proposes future research.

"A strong conclusion is like the final brushstroke on a masterpiece—leave your reader with clarity, impact, and a reason to care about your study."

Key findings are clearly summarized.

Importance and relevance are reiterated.

Implications for research, practice, or policy are discussed.

Limitations are transparently acknowledged.

Future research directions are suggested.

Ending statement is strong, memorable, and impactful.

Conclusion ties together the entire review logically and convincingly.

Discussing the future scope in your review paper involves identifying potential areas for further research, advancements, or applications based on the findings and gaps identified in your review. It offers insights into the potential directions the field could take and highlights opportunities for future exploration and innovation.

Begin by identifying emerging trends or areas of interest within the field that have not been extensively explored. Look for patterns or recurring themes in the literature that suggest new avenues for research or applications.

Discuss unanswered questions or unresolved issues highlighted in your review. Consider why these gaps exist and propose potential research questions or methodologies to address them in future studies.

Propose novel approaches or methodologies that could enhance research in the field or lead to new discoveries. Consider interdisciplinary collaborations or the integration of advanced technologies to overcome existing challenges.

Explore translational applications of your findings for clinical practice, public health, or industry. Discuss how your research outcomes could be translated into tangible benefits for patients, communities, or the healthcare system.

Consider the ethical, social, and policy implications of your research findings. Discuss potential challenges or concerns that may arise from the adoption of new technologies or interventions and propose strategies for addressing them.

Conclude your discussion of future scope with optimism and enthusiasm for the potential impact of future research endeavors. Emphasize the importance of continued exploration and innovation in advancing the field.

By exploring future scope in your review paper, you can inspire readers to think critically about the next steps in research and innovation within the field. By identifying emerging trends, addressing unanswered questions, proposing novel approaches, exploring translational applications, considering ethical implications, and concluding with optimism, you can provide a comprehensive overview of the potential directions for future exploration and advancement.

Identify emerging trends or underexplored areas in your field.

Highlight unanswered questions or gaps revealed in your review.

Propose novel approaches or methodologies to address these gaps.

Explore potential translational applications for clinical, public health, or industrial impact.

Consider ethical, societal, and policy implications of future research.

End with an optimistic statement emphasizing opportunities and innovation.

"More studies are needed to explore this topic."

Problem: Vague, no specifics, lacks actionable insight or vision.

"Emerging trends in nanotechnology and machine learning present exciting opportunities for targeted drug delivery and personalized medicine. Despite progress, critical gaps remain, such as understanding the environmental triggers of autoimmune diseases. Future research integrating interdisciplinary approaches and advanced analytics could address these gaps, with potential applications in early diagnostics, tailored therapies, and improved patient outcomes. Ethical considerations, particularly in gene editing and data privacy, must guide responsible implementation. By embracing innovation and collaboration, the field is poised for transformative advancements."

Strength: Specific, actionable, forward-looking, addresses impact and ethics.

"Think like a trailblazer—your future scope should map the uncharted paths and inspire others to follow."

Emerging trends in the field are identified.

Unanswered questions or knowledge gaps are clearly highlighted.

Novel approaches or methodologies are suggested.

Translational applications for research outcomes are explored.

Ethical, social, or policy implications are considered.

Optimistic, inspiring conclusion that motivates further research.

Future scope is specific, actionable, and clearly linked to findings of your review.

The Acknowledgement section of a review paper is an opportunity for authors to express gratitude to individuals, organizations, or funding agencies that have contributed to the research or writing process. It allows authors to acknowledge the support, assistance, or resources they have received during the course of their work.

Begin by identifying individuals or organizations that have made significant contributions to the research or writing process. This may include colleagues, mentors, research collaborators, technical support staff, or funding agencies.

Acknowledge any technical assistance or support provided by individuals or facilities that have contributed to the research process. This may include laboratory technicians, research assistants, or staff members who provided technical expertise or resources.

Recognize funding support or financial assistance received from grant agencies, institutions, or organizations that have supported the research project. Provide acknowledgment of any grants, scholarships, or fellowships that have contributed to the funding of the research.

Express sincere gratitude to all individuals or organizations mentioned in the Acknowledgement section. Emphasize the importance of their contributions and the impact they have had on the research project.

Keep the Acknowledgement section concise and focused on the key contributors and supporters of the research project. Avoid including unnecessary details or lengthy explanations.

Optionally, you can include additional statements of appreciation or recognition for specific contributions or personal support received during the research process.

The Funding Statement in a review paper acknowledges the financial support received from grant agencies, institutions, or organizations that have contributed to the research project. It provides transparency regarding the sources of funding and helps to establish the credibility and integrity of the research.

Begin by identifying the specific grant agencies, institutions, or organizations that have provided financial support for the research project. Include the names of any grants, scholarships, fellowships, or awards received.

If grant numbers were assigned to the funding received, include them in the Funding Statement. This helps to provide additional information for readers who may wish to reference the specific grants.

Acknowledge any institutional support or resources provided by the author's affiliated institutions or research centers. This may include access to facilities, equipment, or other resources necessary for conducting the research.

If the research project required compliance with specific regulations or guidelines related to funding, include any relevant compliance statements in the Funding Statement.

Identify individuals or organizations who contributed intellectually or technically.

Acknowledge technical assistance or research support received.

Recognize financial support, grants, or scholarships.

Express sincere gratitude to all contributors.

Keep the statements concise and focused.

Optionally include personal acknowledgments, such as family support.

"Thanks to everyone who helped."

Problem: Too vague; lacks specificity about contributors or funding.

"We sincerely thank Dr. [Name] for guidance, [Name] for technical assistance, and our families for their support. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [grant numbers XXXXXX, YYYYYY] and additional support from [Institution/Department]. Their contributions were essential to the completion of this review."

"Always be specific—naming contributors and funding sources shows professionalism and ensures proper recognition. Conciseness is key: clarity > length."

Contributors (mentors, collaborators, technical staff) identified.

Funding sources and grant numbers clearly stated.

Institutional support acknowledged.

Expressions of gratitude included and concise.

Optional personal acknowledgments added if relevant.

Learn to maintain transparency and integrity through proper disclosure of potential conflicts in your review paper.

The Conflict of Interest (COI) Statement in a review paper discloses any financial or personal relationships that may have influenced the research or the interpretation of its results. It is important for maintaining transparency and integrity in scholarly publishing. Here's how to effectively write a Conflict of Interest Statement for your review paper:

Conflict of Interest statements are crucial for maintaining the credibility and trustworthiness of scientific research. They help readers understand potential biases and evaluate the objectivity of the findings. Transparency in reporting conflicts builds trust with the scientific community and the public.

The Conflict of Interest Statement in a review paper provides transparency regarding any financial or personal relationships that may have influenced the research or its interpretation. By disclosing financial relationships, declaring personal relationships, addressing institutional affiliations, specifying funding sources, providing a disclosure statement, and reviewing journal guidelines, authors can effectively address potential conflicts of interest and maintain integrity in scholarly publishing.

Identify any financial relationships or affiliations that could influence the research.

Declare any personal relationships that might affect objectivity.

Note institutional affiliations that could introduce bias.

Specify funding sources and clarify whether they influenced the study.

Write a concise disclosure statement summarizing potential conflicts.

Review journal guidelines to ensure compliance with COI requirements.

Problem: Too vague; does not specify types of potential conflicts.

Strength: Comprehensive, specific, and addresses all potential areas of conflict.

"Transparency is critical—never assume a relationship is too minor to disclose. Clear COI statements protect your credibility and the integrity of your research."

Draft a comprehensive conflict of interest statement for a hypothetical research project. Consider various scenarios including funding from industry partners, institutional affiliations, personal relationships with study participants, and financial interests in related companies. Practice identifying potential conflicts that might not be immediately obvious.

All financial relationships disclosed.

Personal relationships and affiliations addressed.

Funding sources specified and influence clarified.

Statement is clear, concise, and comprehensive.

Complies with journal-specific COI policies.

Reviewed for accuracy and completeness.

Learn the art of proper citation and reference management for credible academic writing.

The References section of a review paper provides a list of all the sources cited within the paper, allowing readers to locate and verify the original sources of information. It is essential for acknowledging the contributions of other researchers and providing credibility to your own work. Here's how to effectively structure and format the References section for your review paper:

Compile citations for all the sources cited within your review paper, including journal articles, books, conference proceedings, websites, and other scholarly works. Use a consistent citation style specified by the journal or publication venue.

Arrange the citations in alphabetical order by the last name of the first author. If multiple works by the same author are cited, arrange them chronologically by publication year.

Provide complete citation details for each source, including the author(s), publication year, title of the work, publication venue, volume/issue (for journals), page range, and DOI or URL (if available). Follow the formatting guidelines specified by the journal or publication venue.

Verify the accuracy and consistency of the citation details, including spelling, punctuation, and formatting. Ensure that all citations are properly formatted according to the citation style guidelines.

Check the specific requirements of the journal or publication venue where you plan to submit your review paper for any additional formatting or citation style requirements.

Include Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) or URLs for online sources whenever possible. This allows readers to easily access the original sources of information.

Each type of reference follows a specific format, including details such as author(s), publication year, title, source, and URL or DOI. It's important to use the appropriate citation style (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago) and format the references accordingly to maintain consistency and accuracy in academic writing.

Each citation style has its own specific rules for formatting in-text citations, reference lists, and bibliographic details. It's essential to consult the appropriate style guide or manual for detailed instructions on citing sources according to the chosen citation style.

Software programs designed to assist researchers and writers in generating citations and managing bibliographic information. Here are some commonly used electronic aids to citation:

Many library databases and catalogs offer citation tools that allow users to export references in various citation formats or generate citations directly from search results.

Gather all sources cited in your review: journal articles, books, book chapters, conference proceedings, theses, websites, reports, government publications, newspapers, and magazines.

Select a citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, Harvard, Vancouver, IEEE) and stick to it consistently throughout your work.

Order citations alphabetically by the first author's last name; for multiple works by the same author, order chronologically.

Provide complete citation details: authors, year, title, source, volume/issue, pages, DOI/URL.

Check accuracy of spelling, punctuation, and formatting. Use reference management tools for efficiency.

Problem: Incomplete information, unclear source, no formatting.

Strength: Complete, properly formatted, provides clear bibliographic details.

"Accurate references are the backbone of credibility. Always double-check author names, publication year, and DOIs."

Practice creating references for different source types using your chosen citation style. Start with 5 different types of sources and verify each citation against the style guide. Use reference management software to streamline the process and ensure consistency.

All cited sources are included in the reference list.

Citation style is consistent throughout (APA, MLA, etc.).

Sources are arranged alphabetically by author.

Complete citation details are provided (authors, year, title, journal/book, volume/issue, pages, DOI/URL).

Spelling, punctuation, and formatting accuracy verified.

Include DOIs or URLs for online sources.

Learn to create effective tables, figures, and visual elements that enhance your review paper's impact and readability.

Visual elements such as tables, figures, graphs, and flowcharts play a vital role in a review paper. They make complex information easier to understand and allow readers to grasp the essence of the content quickly. By presenting data visually, large amounts of information can be summarized in a compact form, which reduces the need for lengthy descriptions. This not only saves space but also improves the overall clarity of the paper.

Visuals also help in highlighting important patterns, comparisons, and key findings that may not be immediately obvious in plain text. For instance, a graph can clearly show trends over time, a table can compare multiple studies side by side, and a flowchart can present a step-by-step process. Such elements guide the reader's focus, making the paper more engaging, organized, and professional. In essence, visual elements transform raw data into meaningful insights, thereby strengthening the impact of the review.

A table showing antioxidant plants, their active compounds, and reported effects.

A bar chart showing the percentage of studies supporting antioxidant activity of different plant extracts.

A flowchart showing inclusion and exclusion steps in literature screening.

Tables are an effective way to organize and present information clearly. They are most useful for summarizing study details, making comparisons, and presenting classifications in a structured manner. For instance, a table can help readers quickly compare the methodology or findings of multiple studies side by side without having to read through long paragraphs.

Each table should have a clear and descriptive title that tells the reader exactly what the table represents. Similarly, column headings should be precise, and if numerical data is included, all units of measurement must be mentioned to avoid confusion.

Consistency in formatting is also important — use uniform font style, spacing, and alignment so that the table looks professional and easy to read. Overly complicated or cluttered tables should be avoided, as they reduce clarity instead of enhancing it.

Finally, whenever a table is created using information or data adapted from published work, the original sources must be cited properly. This not only gives credit to the original authors but also ensures academic integrity and reliability of the review.

Figures are powerful tools to visually communicate complex ideas and processes. They may include diagrams, flowcharts, chemical structures, or conceptual models, each serving a different purpose. For example, chemical structures can help illustrate active compounds, while flowcharts and conceptual models are ideal for explaining mechanisms, pathways, or research frameworks.

Every figure should be accompanied by a descriptive caption that is clear and self-explanatory, allowing the reader to understand the figure without needing to search the main text for context. Captions should mention what the figure represents and highlight key elements.

It is equally important to ensure that figures are prepared in high-quality resolution, especially if the review is aimed for publication. Low-quality or pixelated figures reduce readability and may not meet journal standards. Using clean, well-labeled, and professionally designed figures makes the review more engaging and scientifically reliable.

Graphs are especially useful when the goal is to present trends, statistics, and relationships in a way that readers can quickly interpret. They transform raw numbers into meaningful visuals, making complex data much easier to understand at a glance.

The choice of graph should depend on the type of data: a bar graph for comparing categories, a line chart for showing changes over time, a pie chart for proportions, and a scatter plot for identifying correlations or distributions. Selecting the right graph type ensures that the information is represented accurately and clearly.

All graphs must have well-labeled axes and clear legends so that the reader can interpret the data without confusion. Labels should include measurement units where applicable. Clarity should always be prioritized — avoid cluttered, overly detailed, or overdecorated visuals that distract from the actual findings.

A well-designed graph enhances the professional quality of the review, highlights key trends, and helps readers quickly grasp the significance of the results being discussed.

The visual representation of literature is a powerful method for analyzing and presenting complex literary data and concepts. Three highly effective tools for this purpose are conceptual maps, timelines, and comparative charts, each serving a distinct analytical function.

A Conceptual Map (or mind map) is best used to visually articulate thematic links within and across literary works. By placing the core subject (an author, text, or main theme) in the center, related concepts like sub-themes, motifs, or literary devices can branch out.

For demonstrating chronological progression, a Timeline is the indispensable tool. This visualization is used to present the sequence of events, publication dates, or the development of an entire literary movement. A well-constructed timeline must clearly define its scale (e.g., decades) and mark significant points such as the publication dates of seminal works, key biographical events for an author, or major historical shifts that shaped the literature. Timelines are particularly useful for tracking the evolution of an author's style over a career or charting the rise and fall of a specific genre, such as Modernism.

Finally, Comparative Charts (matrices or tables) are the optimal method for synthesizing existing scholarship and, crucially, highlighting research gaps. By structuring the chart with scholarly articles listed in the rows and analytical criteria (like Theoretical Approach Used or Focus Texts) in the columns, the researcher can achieve an immediate, side-by-side assessment of the current state of the field. A research gap is visually indicated when a specific column—representing an unexamined theory or methodology—remains blank across all reviewed studies. For example, if all existing studies use Marxist and Feminist theory, an empty column for Postcolonial theory instantly reveals an area ripe for future exploration.

Credibility in academic publishing hinges on transparency. Any visual content that is not purely original to the author—whether directly reproduced, modified, or simply inspired by another work—must be appropriately attributed.

If you use a figure exactly as it appeared in its source, the caption must include a full bibliographic citation and the necessary copyright attribution statement.

If you recreate a chart, redraw a model, or change the colors/layout of an existing figure (a process known as creating a derivative work), you must explicitly acknowledge this in the figure caption using phrases like "Adapted from..." or "Based on..." followed by the original source citation. This is a critical ethical practice, as intellectual property rights protect the original creative expression and design of the visual, even if the underlying data is public.

Copyright law grants the creator (often the publisher, after assignment of rights) the exclusive right to reproduce their work. Therefore, using a figure from a copyrighted source requires formal permission.

Beyond ethics and law, practical compliance with journal standards is essential to ensure your paper is accepted and the visuals are clearly legible in print and digital formats.

Figures must meet the journal's minimum resolution requirements (typically 300 dpi or higher) to avoid pixelation. They must also fit within the journal's mandated single-column or double-column width constraints.

Journals specify acceptable file types (e.g., TIFF, EPS, PDF, or high-quality JPEG). Using the correct format ensures the figure is processed correctly during the publication phase.

Ethically, figures should be designed for maximum readability, including using colorblind-safe palettes and providing clear, descriptive captions and labels.

Master the final steps to successfully publish your review paper in a reputable journal.

Selecting the appropriate publication venue is crucial, as a mismatch between your paper and the journal's focus is one of the most common reasons for immediate rejection. This decision should be guided by three main considerations:

The Aims and Scope section on a journal's website is the single most important factor. You must confirm that your research topic, methodology, and conclusion fit precisely with the journal's declared interests. Submitting an empirical study to a journal that only publishes theoretical reviews, or sending a highly specialized literature review to a broad, general-interest publication, is a guaranteed rejection. A perfect match ensures your paper reaches the editors and peer reviewers who are experts in your exact field.

Impact Factor (IF) and Indexing: The Impact Factor (or similar metrics like CiteScore) indicates the average number of citations articles in that journal receive, signaling its prestige and influence. Indexing (e.g., in Web of Science, Scopus, or PubMed) ensures your work is discoverable and citable by the wider academic community. High IF journals have higher rejection rates and are best suited for groundbreaking research, while targeted, specialized journals may offer a better chance for focused work.

Audience: You must decide who you are trying to reach. A highly specialized journal will directly target a small group of experts, leading to high-quality, relevant citations. A broad or interdisciplinary journal will allow your work to reach a wider, non-specialist audience, which may be desirable if your findings have wide-ranging applications. The language and style of your manuscript must be tailored to the chosen audience.

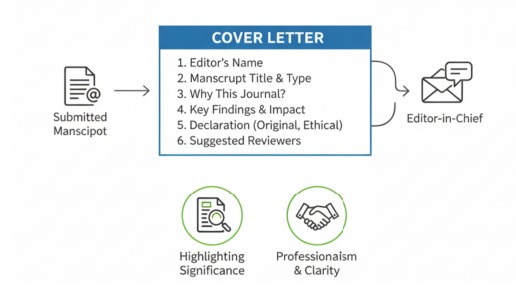

Beyond the formatted manuscript, a successful submission requires several key accompanying documents:

This is your formal introduction to the journal editor. It must be concise but persuasive, stating the title of your work, affirming that it has not been previously published and is not under consideration elsewhere, and clearly explaining why your research is a perfect fit for the journal's scope and why it will be of interest to their readership. You should also mention any ethical approvals and confirm that all authors have approved the submission.

Many journals require each author to individually submit a form confirming their contribution meets the criteria for authorship (e.g., as defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, ICMJE). All authors must also explicitly declare any potential financial or personal conflicts of interest (or state that none exist) to maintain transparency and integrity.